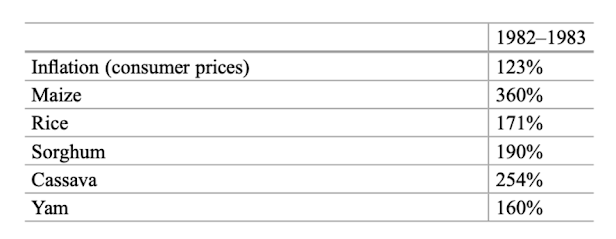

As you may know, in 1983 Ghana experienced the worst drought in modern history, and consequently widespread famine. Since 1981 there had been very little rainfall, and when it had rained it was at the wrong place or time, producing one of the harshest droughts the nation had ever seen. Without any irrigation, rainfall determined the output and livelihoods of the majority of the population, subsequently resulting in food insecurity. At this point in time the agricultural sector employed over 50% of the labour force and made up nearly 60% of the nation's gross domestic product making the famine even more severe. In 1983, the majority of Ghana received less than 50% of its normal rainfall totals, with Accra (the coastal region) having 58% of its usual rainfall and extensive bushfires occurring in the North. It was reported that up to 35% of total food production was destroyed across the nation. Two of the three major crops (maize and millet) declined by over 50% and in the South both food crops and cacao were negatively affected. The consequences of the drought and food insecurity meant that per capita caloric consumption decreased to 65% and an increase in food price meant the poorest were the most negatively affected (Figure 1). However, it is difficult to examine the full effects of the famine in Ghana, because it is an area considerably understudied.

|

| Figure 1: Food price inflation in Ghana during the drought of 1982-1983 |

| ||

Figure 2: The agro-ecological regions of Ghana

|

Please watch this video for an overview of the current agricultural landscape of Ghana, including economic impacts, exports, expansion of agricultural production and reasons for intervention.

Future for Ghana

A way forward?

Studies have highlighted the links between drought vulnerability in Ghana to socio-economic development and spatial differentiation. Therefore, it would make sense for climate adaptation policies to be specific to regions based on their level of vulnerability. For example, The North, Upper East and Upper Western farming communities of Ghana depending on rain-fed agriculture and most vulnerable to climatic changes, could be introduced to other means of income, away from farming. Such evidence from these studies, indicate that policymakers should create specific and targeted climate adaptation policies aimed at reducing the vulnerabilities of Ghanian farmers depending on raid-fed agriculture. This would maximise drought preparedness in the most vulnerable farming regions of Ghana.

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteInteresting post! I did not know Ghana grew such a wide variety of crops in its different regions. I was wondering whether any specific measures have already been implemented in anticipation of more extreme flooding and droughts?

ReplyDeleteThanks Emma! Ghana is currently looking into the prospect of GM crops and growing drought-resistant crops. So far, the government is working on rehabilitation of irrigation facilities across the nation and are funding the construction of 240 earth dams that look to support farming all year round. The government also has officers deployed to introduce farmers to climate-resilient interventions such as crop rotation, compost fertilisers and intercropping. There is a government programme called “planting for food and jobs” which is currently undergoing role out with climate adaptation initiatives being included. Although this is a good start, Ghana must continue to look into rain-harvesting technologies, as the nation can no-longer rely on rain-fed agriculture.

Delete